Part 1: A — What am I really?

In yoga, we are told that our true nature is Eternal, Pure Consciousness.

Patanjali says:

“Draṣṭuḥ svarūpe’vasthānam” — (Through yoga) the Seer abides in its own true nature.”

Ancient yogic texts echo this truth through the mahāvākyas, the great declarations of Truth:

“Aham Brahmāsmi” — I am Brahman, the ultimate reality.

“Tat Tvam Asi” — You are That, the eternal self.”

It’s a profound idea — but what does it actually mean?There is a vast distance between understanding something — and living it.

When I turn inward… I don’t see Brahman.

In theory, it sounds beautiful — I am eternal. I am pure consciousness. But in practice, I keep mistaking my thoughts and emotions — as me. I keep identifying with the changing — not with the eternal.

I see my thoughts — they rise and fall.

I get hurt — and pain consumes my mind.

I get hungry — and food becomes the goal.

I feel stressed — and thoughts begin to spin — Around my work, around my home, Around the things I can’t control.

I am told I am the Seer — unchanging, untouched. But I keep getting caught in what I see.

Where is the Seer in all of this?How do we experience that eternal, pure consciousness?The answer, for me, begins with a sound.Not just any sound — but one that is said to contain the essence of all others. The sound of Oṁ.

Fun Fact:

You’ve probably heard this popular quote:

“The Body is the bow, Āsana is the arrow, and the Soul is the target.” — B.K.S. Iyengar (Guruji)

But did you know the origin of this comes from the Upaniṣads?

“Oṁ is the bow, the Self is the arrow, and Brahman is the target. When the target is struck with an undistracted mind, the seeker becomes one with Brahman.” — Muṇḍaka Upaniṣad (2.2.4)

To strike that inner target, we must steady the mind and draw the string inward — as if turning away from the distractions of the world.

We sharpen our focus, like the tip of the arrow.

And when we release the string, we let go of all desires.With single-pointed focus (ekāgrata), the seeker merges with the target — the Inner Self.

Part 2: U — How do I turn Inward?

We begin every class with the sound of Oṁ.

It's a familiar ritual. We sit quietly, close our eyes, and chant.

At first, it might feel like a formality — something we do because it’s always been done.

But over time, we notice something subtle happening.

The noise inside begins to settle.

The breath becomes more even.

The mind begins to draw inward.

There’s a shift within ourselves.

So what exactly are we doing when we chant Oṁ?

Patañjali, in the Yoga Sūtras, introduces Oṁ not just as a sound, but as a direct means of connecting with the inner Self.

Patañjali’s Oṁ Sūtras:

1.27: “tasya vācakaḥ praṇavaḥ” —

The word expressing That (Īśvara - Eternal Consciousness) is Oṁ (Praṇava).1.28: “taj-japas tad-artha-bhāvanam” —

(Don’t just chant it mechanically.) Repeat it (japa), and meditate on its meaning (artha) with feeling/ emotion (bhāvana).1.29: “tataḥ pratyak-cetanādhigamo’py antarāyābhāvaś ca” —

From this (chanting with meaning and feeling), comes the realization of the inner consciousness (pratyak-cetanā) — and the falling away of obstacles (antarāyā).

It’s a bold promise.

Repeat Oṁ with meaning and feeling — and you’ll begin to reach the Self.

The disturbances that cloud the mind will lose their grip.

The Power of Oṁ:

Once, someone asked Sharada Devi:

“Mother, the mind is very restless. I can’t steady it in any way.”

She replied:

“As the wind removes the clouds, so the name of Īśvara (Oṁ) destroys the clouds of worldliness.”

This leads us to a deeper question:

What is the meaning of Oṁ?

If Patañjali asks us to reflect on the meaning, what exactly are we supposed to be reflecting on?

For that, we look to a different text — one that goes deeper into the nature of this sound.

Short Story: The Shortcut of Oṁ

Hanuman once asked Shri Rama, “How can I realize my true nature?”.

Shri Rama’s reply was simple: “Māṇḍūkyaṁ ekam eva alam” —

The Māṇḍūkya Upaniṣad alone is sufficient.

If that is too difficult, then study these 108 Upaniṣads.

Māṇḍūkya Upaniṣad is a short text of just 12 powerful compact verses.

It tells us what Oṁ means and how it reveals the Self.

It’s the foundation for chanting Oṁ with artha-bhāvanam —

meaning and feeling.

Let’s try our best to study this short Upaniṣad, —

so that we don’t have to go through 108.

Part 3: Ṁ — What is hidden within the Sound?

Sanskrit Grammar

In Sanskrit, there's a grammatical rule called Sandhi, which governs how sounds combine.

One such rule is: A + U = O

(Pronounced: A as uh, U as in oo)We see this in many āsana names. For example:

Pārśva + uttānāsana = Pārśvottānāsana

Padma + uttānāsana = PadmottānāsanaIn the same way:

A + U + Ṁ = OṀ

The Māṇḍūkya Upaniṣad teaches that Oṁ is not just a sound, but the entire journey of consciousness itself. It breaks down the syllable Oṁ into four parts — A, U, Ṁ, and the Silence that follows — each one revealing a deeper layer of our experience.

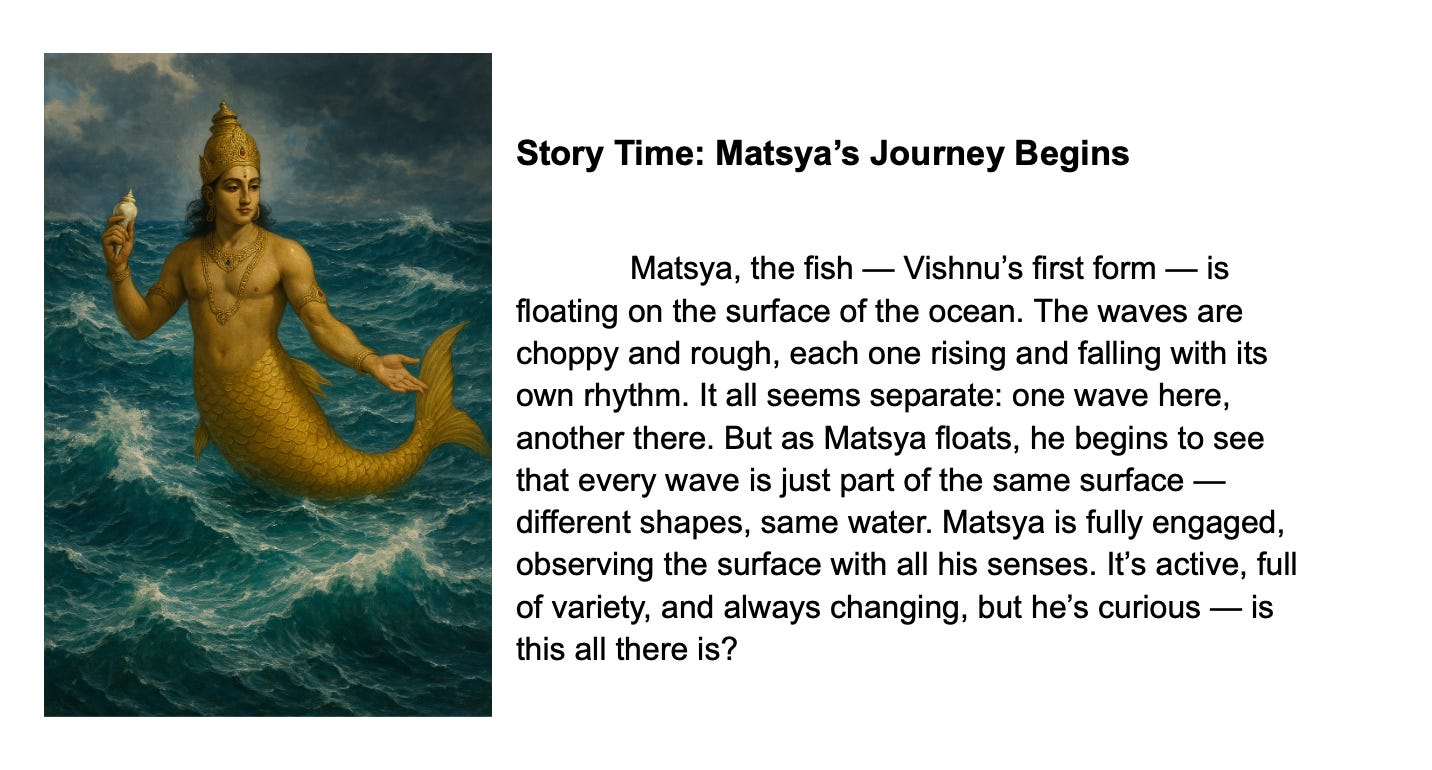

A — Waking State (Jāgarita Avasthā)

Introduction:

The sound A represents the waking state — the first sound we make when opening the mouth, just as waking is our first experience of the world. Here, consciousness turns outward through the senses.

Individual Self:

The self in this state is Vaiśvānara, described in the Upaniṣad as having “nineteen mouths” — the five sense organs (jñānendriya), five organs of action (karmendriya), five vital forces (prāṇa), and the four parts of the inner instrument (antaḥkaraṇa): mind (manas), intellect (buddhi), ego (ahaṅkāra), and memory (citta).

Cosmic Form:

The cosmic form is Virāṭ — the total waking consciousness, made up of all individual selves. The Upaniṣad describes Virāṭ as having “seven limbs” —

heaven (head), sun (eyes), air (breath), fire (heart), water (stomach), earth (feet), and space (body) — symbolizing how the entire physical universe is the manifested body of the Self.

Associated Body:

This state corresponds to the gross body (sthūla śarīra) — the outermost layer of experience, shaped by matter and form.

Philosophical Significance:

Though we take the waking state as real, it is only transactional reality (vyavahārika) — conditioned by time, space, and causality. The Self appears divided in this state, but this is just the surface of a deeper, unified reality.

Chanting with Meaning and Feeling (artha-bhāvana):

While chanting A, we bring awareness to our waking identity — as Vaiśvānara, navigating life through body and senses. The sound resonates in the throat, expanding outward, just like our awareness in waking life. We reflect on the waking world and our identity in it, then step back to realize: this is merely an object of our consciousness.

The Upaniṣad says that one who meditates on A as Vaiśvānara “obtains all desires” — recognizing the Self in all forms and aligning with the source of creation.

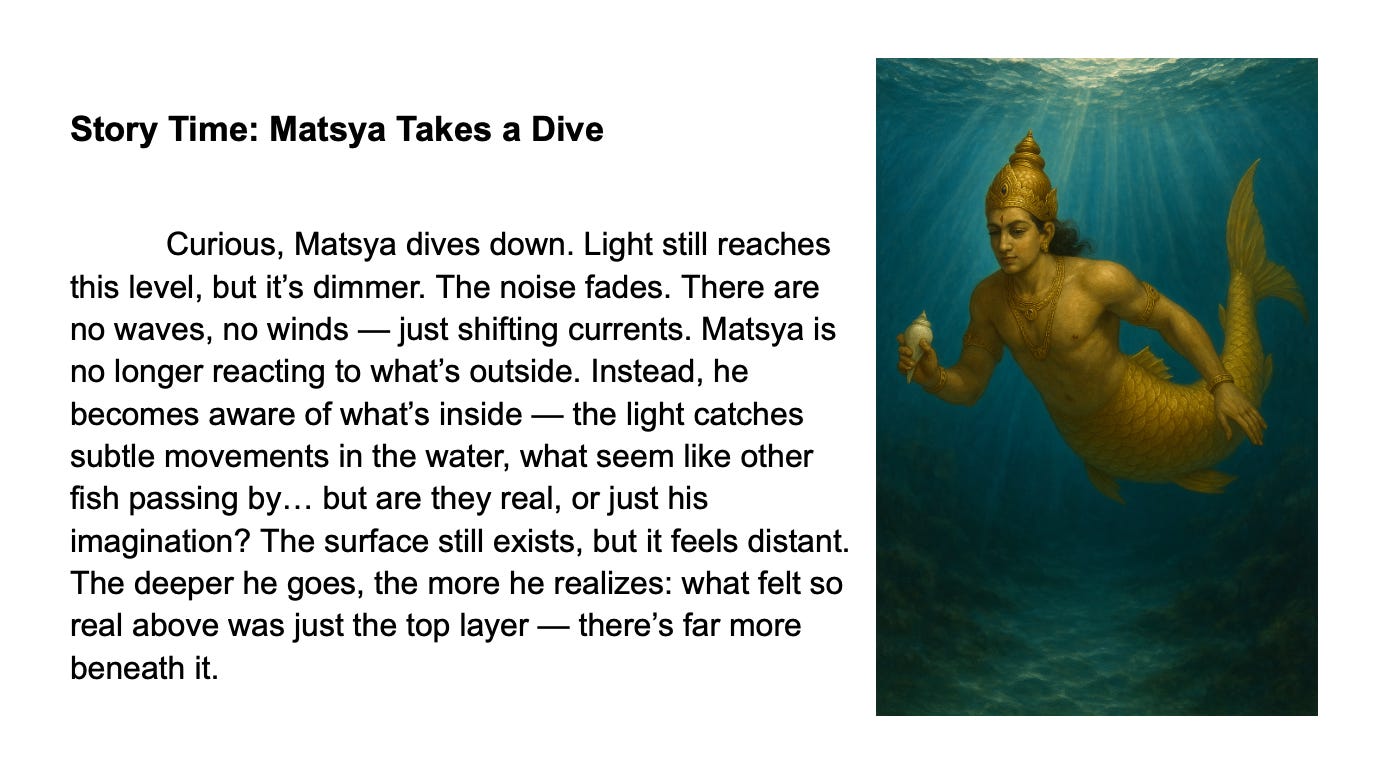

U — Dreaming State (Svapna Avasthā)

Introduction:

The sound U represents the dreaming state. It follows A in the flow of sound — moving from the open throat toward the palate. Similarly, this state is subtler than waking, as consciousness turns inward toward mental impressions, images, and memory. The senses and outer world are shut off, and the mind creates an internal world.

Individual Self:

The self in this state is Taijasa, meaning “the luminous one,” as it illuminates the inner world of dreams — thoughts, impressions, and memories — without external input. The dreamer functions through the same “nineteen mouths” as in waking, but now turned inward.

Cosmic Form:

The cosmic form is Hiraṇyagarbha — the “Golden Womb,” the total subtle mind that holds and projects the universe in its unmanifest form. Just as Virāṭ is the macrocosm of the physical world, Hiraṇyagarbha is the macrocosm of all thoughts, imaginations, and possibilities.

Associated Body:

This state corresponds to the subtle body (sūkṣma śarīra) — the realm of thoughts, feelings, prāṇa, and mental activity. Though invisible, it shapes and animates the physical form.

Philosophical Significance:

In this state, the Self is withdrawn from the external world, but still caught in impressions and duality. Dreams may seem real while they last, but arise and dissolve within the mind. This reveals a deeper truth: just as dreams are mental projections, even the waking world is ultimately a projection within Consciousness.

Chanting with Meaning and Feeling (artha-bhāvana):

As the sound moves to U, awareness turns inward. We contemplate Taijasa, the luminous dreamer within. The sound glides along the palate, drawing attention away from the senses and toward the mind. We enter the subtle realm where thoughts, memories, and inner imagery arise — an interior landscape more inward than the last.

The Upaniṣad says that one who meditates on U as Taijasa “attains a superior understanding” — expanding the mind, refining awareness, and preparing it for deeper stillness.

Ṁ — Deep Sleep State (Suṣupti Avasthā)

.Introduction:

The sound Ṁ represents the deep sleep state. When chanting Oṁ, A and U naturally dissolve into Ṁ — the lips close, and the vibration deepens. In this state, the senses, mind, and all mental activities become dormant. There are no dreams, no thoughts, no distinctions — only an undivided, undisturbed rest. It is a latent, potential-filled state of blissful stillness.

Individual Self:

The self in this state is Prājña, meaning “the wise” or “the knowing one.” In deep sleep, there is no sense of self or other — only a quiet, potential state. The self experiences bliss (ānanda) and rests in the seed form of all experiences. Though there is no awareness of duality, the latent tendencies (vāsanās) remain. Prājña is described as a “mass of consciousness,” undivided and still.

Cosmic Form:

The cosmic form is Īśvara — the Lord or inner controller of the universe in its causal state. Īśvara is the totality of all potential — the cosmic cause from which both the waking and dream states emerge, and into which they dissolve. The Upaniṣad calls Prājña “the source of all, the omniscient, the inner controller, from whom all beings originate and into whom they return.”

Associated Body:

This state corresponds to the causal body (kāraṇa śarīra) — the deepest layer of embodiment, where all experiences lie dormant in seed form. It is not a body in the physical sense, but the subtlest sheath — the undivided ground of becoming.

Philosophical Significance:

Here, the Self is beyond thought and form, but not yet fully realized. There is no awareness of “I am sleeping,” but there remains a trace of ignorance (avidyā) — a veil that obscures true knowledge. Deep sleep offers a glimpse into the peace of unity, but without conscious recognition. It is a gateway: from here, one can either return outward (to dreaming or waking), or continue inward toward realization.

Chanting with Meaning and Feeling (artha-bhāvana):

As the lips close on Ṁ, we sense completion and absorption. The sound hums softly, resonating deep within — much like the experience of deep sleep. We reflect on Prājña, the blissful, undivided state where all mental activity ceases. While chanting Ṁ, we let go of our stories, identities, even thoughts — allowing everything to dissolve into one undisturbed presence.

The Upaniṣad says that one who meditates on Ṁ as Prājña “is able to comprehend all and absorb all into themselves.” It offers a taste of unity — where all differentiation merges into the stillness of pure potential.

Silence — Pure Consciousness (Turīya)

Introduction:

After the sounds A, U, and Ṁ dissolve, what remains is silence — not emptiness, but fullness without form. This is Turīya, the “fourth,” which is not a state like the others, but the ever-present background of all experience. It is not something we enter or exit, but that which underlies and transcends waking, dreaming, and deep sleep.

Individual Self:

Turīya is not an individual state, but the true Self (Ātman) — pure awareness that is unchanging, undivided, and ever-present. It is not conditioned by time, space, or causality. In Turīya, the Self is fully itself — not projected into forms or roles.

Cosmic Form:

There is no cosmic form in Turīya, because form belongs to the other states. Turīya is beyond the manifest and the unmanifest. It is not a part of creation, but the unchanging reality (Brahman) that illuminates all states without being affected by them.

Associated Body:

Turīya is beyond all bodies. It is śarīra atīta — transcending the gross, subtle, and causal. There is no sheath here, no activity, no limitation. Only pure being, awareness, and bliss.

Philosophical Significance:

The Māṇḍūkya Upaniṣad says Turīya is “unseen, beyond relation, incomprehensible, ungraspable, undefinable.” It cannot be reached through thought, imagination, or even experience — because it is the witness of all these. It is “one without a second,” the only reality. The other three are states — they come and go. Turīya alone always is.

Chanting with Meaning and Feeling (artha-bhāvana):

After the audible chant of Oṁ ends, we remain in silence — aware, alert, and undistracted. This is the most important part of the practice. We rest in that stillness, not as an observer of it, but as it. This is the doorway to Turīya — pure awareness free of thought, form, and identification.

The Upaniṣad says that one who abides in Turīya “is the Self, the fearless Absolute.” In this silence, the seeker no longer chases after knowledge or bliss — they realize themselves as the foundation of both.

Part 4: Silence – How to Bring Oṁ into Yoga Practice and Teaching?

Oṁ in Practice

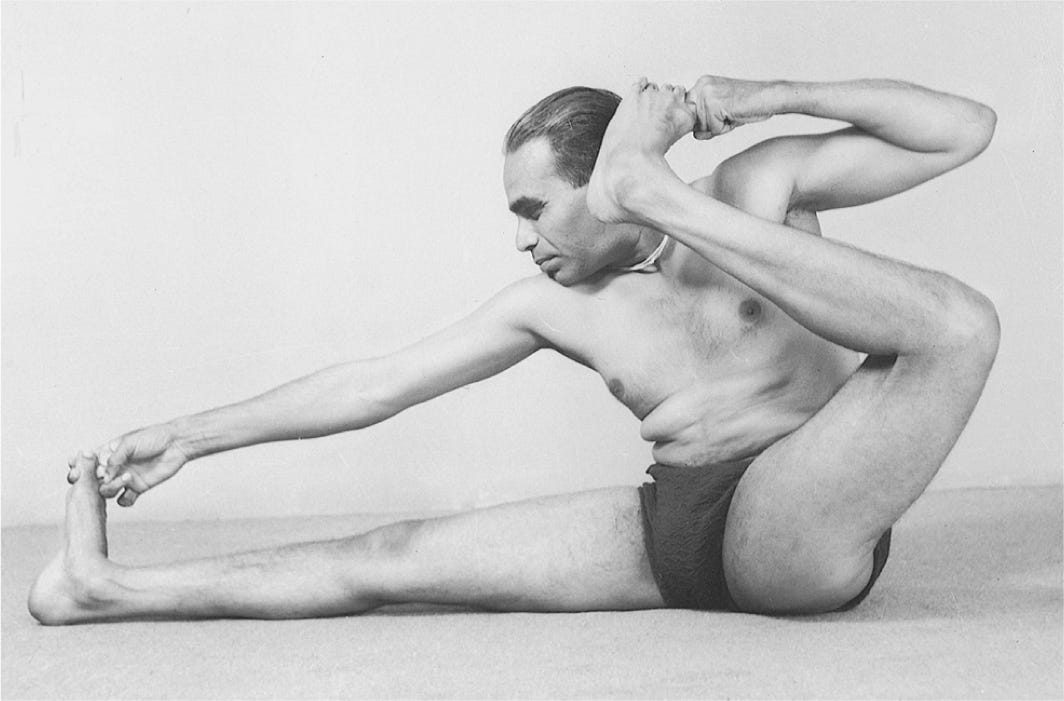

A — Level 1: Effort and Form

In the beginning, practice is about doing.

“Straighten the arms,” “Roll the thighs in,” “Press the heels down.”

We focus on alignment, stability, and clear action.

Awareness is directed outward, into the form — just as in the waking state.

U — Level 2: Awareness and Sensitivity

With repetition and attention, something shifts.

Instructions aren’t just heard — they’re absorbed.

The intelligence of the body awakens.

We begin to feel the pose from within. The mind turns inward.

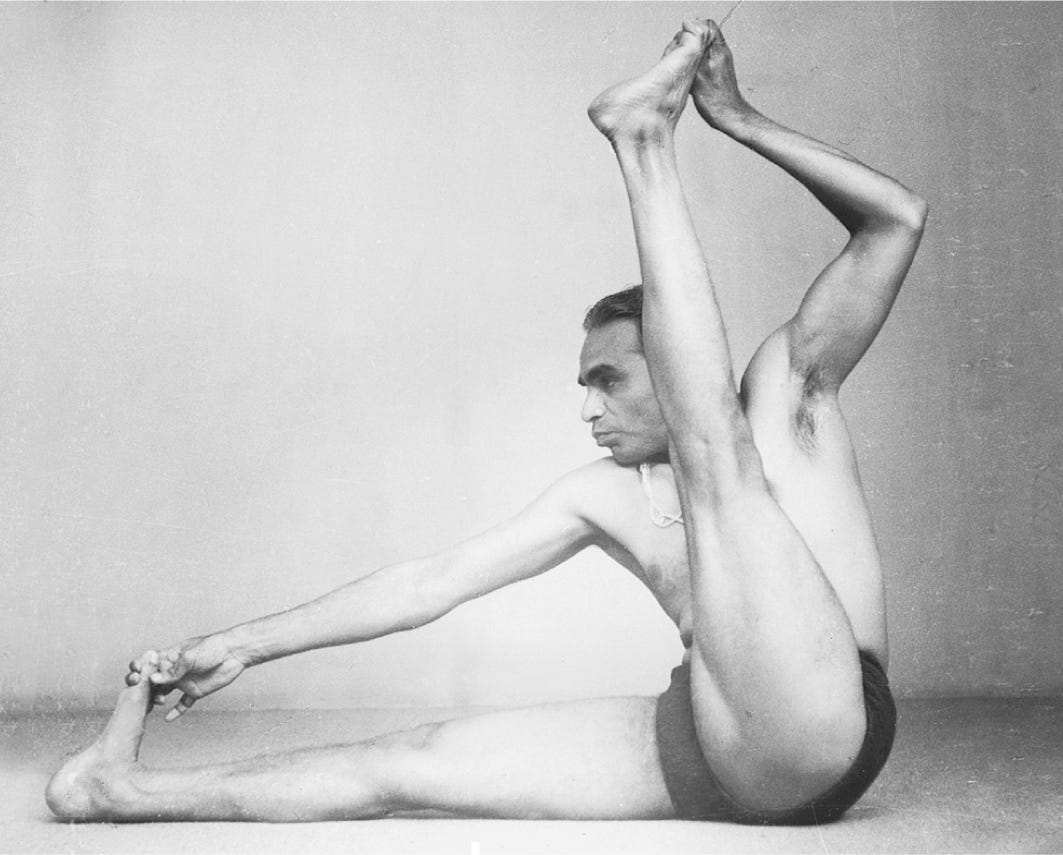

Ṁ — Level 3: Integration and Transformation

Deeper patterns begin to change.

Habitual tensions release. Effort gives way to absorption.

Old Saṃskāras begin to lose their grip.

Practice becomes a process of inner transformation.

Silence — Level 4: Effortlessness and Abidance

Eventually, action dissolves into awareness.

There is no longer “doing” the pose — the pose is.

A stillness arises where the Seer can simply remain.

Practice becomes a doorway to the Self, where stillness gives rise to insight.

Oṁ in Teaching

A — Level 1: Plane of Physicality

We begin by teaching form and alignment.

“Extend the legs,” “Lift the chest,” “Press the heels.”

These instructions build clarity, discipline, and familiarity.

This is teaching from the gross layer — establishing the foundation.

U — Level 2: Plane of Sensitivity

We guide students to observe and feel.

“Compare the two sides,” “Feel the back ribs,” “Notice the breath.”

Here, the student is invited into their inner space — subtle, nuanced, alive.

The teaching speaks to awareness, not just action.

Ṁ — Level 3: Plane of Perceptivity

We begin to reveal deeper interconnections:

“Notice how your arms affects your shoulder blades,”

“How your breath softens the groin,”

“How effort in one place demands surrender in another.”

Teaching becomes less about correction, more about insight.

Silence — Level 4: Plane of Reflectivity

At the deepest level, teaching arises from stillness and reflection.

We guide students not just to move, but to pause — to observe, to reflect.

Without reflection, there is no yoga.

It is reflection that gives meaning to movement, depth to awareness, and rise to insight.

Final Reflections: Spiritual Archery with Oṁ

Oṁ is not merely a sound we chant — it is a complete map of consciousness, a spiritual archery where Oṁ is the bow, the Self is the arrow, and the Inner Self is the target.

Through A, we begin by knowing the world.

Through U, we turn inward to explore the mind.

Through Ṁ, we rest in the stillness of potential.

Through Silence, we glimpse the unchanging Self.

Questions to Sit With:

When awareness turns inward, what do you encounter first?

The body ages, the mind changes —

Is there something in you that remains constant?What part of you is present in waking, dreaming, and deep sleep?

Can you sense a presence in yourself that is unchanging and ever-present?

Each part of Oṁ offers a doorway — into experience, into practice, into teaching.

They guide us from surface to depths, from action to stillness, from form to presence.

Oṁ does not lead us to something new — it returns us to what we’ve always been.

The Self is revealed when all else becomes quiet.

Let the sound lead you.

Let the silence hold you.

Let the Seer abide in its own true nature.

Oṁ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ

Hariḥ Oṁ🙏🏻

Rohit, I appreciate this essay very much. Did you derive it from commentary on the Māṇḍūkya Upaniṣad? I ask because your scholarship and study are inspiring. I'm curious about your process in writing this. I have a more important question, too. We learn from BKS Iyengar that citta is composed of manas, buddhi, and ahamkara. I always wonder where this idea comes from. Is it the Māṇḍūkya Upaniṣad? I note your description of "the four parts of the inner instrument (antaḥkaraṇa): mind (manas), intellect (buddhi), ego (ahaṅkāra), and memory (citta)." These ideas are all listed together but not with the first three comprising the fourth. I'm very curious where Guruji's notion of citta comes from. Perhaps you can shed some light?

Rohit I really enjoy this article! I read it twice and will most likely study it again😊. It was very informative and next time I chant Om it will be with more understanding and connection ! “ See “ you in the next Gulnaaz class !!

Cathy